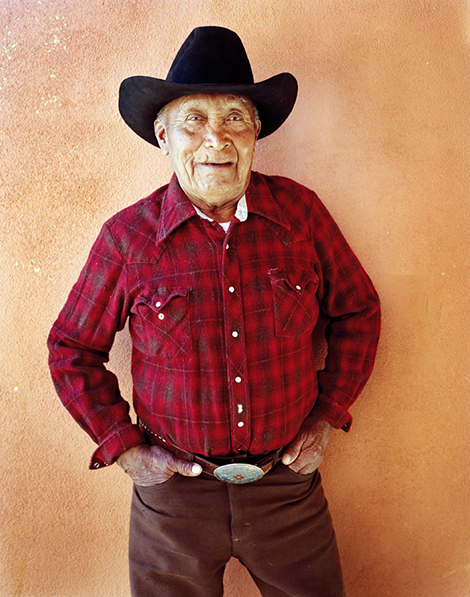

Native American Worker

: Uranium and Native AmericansAn era of cold war started after the World War II between the West and the East. The two sides started arms race, which made uranium supply a critical issue. An area near Four Corners of the U.S., especially Navajo Reservation, turned out to be the richest in uranium in the nation. Uranium mine development started in the 1940s and went into full swing in the 1950s, which continued until the 1980s. During this period, approximately 15,000 miners worked in uranium mines and 30% of the miners and millers were Native Americans. While protective facility and ventilation are absolute requirements for uranium mining, neither the U.S. government nor the mining company issued any warning or prepared protective facility. As the community of the Native Americans had been in dire economic situation after the Great Depression, it welcomed job opportunities with open arms. In almost all family, there was at least one man working at uranium mine. Testimonies of the Native Americans show that miners were left to themselves without a single word of warning when they worked in the uranium mines. Timothy Hugh Benally, who also a uranium miner, in February 1993 recalled the conditions of the Kerr-McGee mines in the Cove area of Red Valley. From his office, He spoke of those days: The working conditions were terrible. Inspectors looked at the vent[ ventilation fans]. When they weren’t inspected, they were left alone. Sometimes the machines[ for ventilation] didn’t work… They told the minors to go in and get the ore shortly after the explosions when the smoke was thick and the timbers were not in place. There was always the danger of ceiling coming down them. The foremen were Anglos[ white men] and rarely went into the mines. I complained about that. I said if we were represented by a union, we’d get our rights. I was fired again. I left it… The people I worked with are now all dead from cancer or other causes… A lot [of those living] have file claims, and some are still waiting. It’s kinda sad to see people come and file claims and their claims are held up for various reasons. We filed some test cases and saw how they are processed. We ‘ll see what happens. The people who worked in the mines started dying in the 1950s. We tried traditional ceremonies to cure the husbands. We tried traditional remedies, and some tried the Native American Church. They gradually went down. They were usually heavyset men, and when they died they were skin and born. The Native Americans who did not receive any protective gear were exposed to uranium radiation, which led to a series of deaths since the 1950s. I met Earl at an association of uranium exposure victims. He is now 48 years old. He said that he lived in a mining village with his father (Herbert D Yazzie), who was a uranium miner. He told me he used to swim and play in puddles or pools near the mine. Probably because of that, he said, all the members of his family suffer from sickness of some sort. His grandfather, father, son and daughter – while all of them go to hospital for temporary treatment, he thinks that they will suffer from pain until the day they die. Many people in a village near Tuba City contracted with cancer due to contamination by subsurface water from uranium. For miners, the most commonly contracted disease is lung cancer, along with many other sicknesses that are difficult to identify. What is urgent now is reclaiming abandoned mine lands. In Navajo alone, there are about 1,100 uranium mines. These mines which are of various sizes used to be called ‘dog holes’ in the past and animals still drink water from puddles scattered around the mines not reclaimed yet. In a village in Cove, Arizona, there were only a couple of children and widows left, because all their husbands passed away. While some things in life are forgivable, others are not. Can this be forgiven? Then, who should be the ones to be forgiven? These people try to console themselves, by saying that they are simple victims of the cold war. Regarding the situation, the U.S. does not show any signs of change. In 2005, the U.S. government and the Congress passed an act to allow new uranium mine development within the Reservation. Gatherings of victims are always filled with constant weeps and moaning of the widows. Phil Harrison, a young Navajo I met there, is committed to dedicate his whole life to fight for Navajo victims’ families. His father was a uranium miner and died of lung cancer. Though new victims have constantly appeared since his father’s death, the Navajos just immersed in sorrow and did not take any action. He decided that someone should try to resolve the problem. He rolled up his sleeves and gathered information. Now he runs ReCa Field Office; Radiation Exposure Compensation Act. In this office, he collects and organizes the policies of the U.S. government, their implications, and legal terms, and then, communicates the details to the Navajos, traveling to various villages in the Reservation. This led him to travel over 200,000 miles (320,000 kilometers) within the Reservation over the past 4 years. After inauguration of William Clinton as President of the U.S. in 1994, Committee on Human Radiation Experiments was established. When the victims came to New Mexico, the truths and testimonies started to be recorded in Red Tape. Tribal government policy in the Reservation states that there will no more uranium mine. However, the rift between Navajo community and the federal government has been deepening. Currently, the tribal government has been striving to raise this as an international issue, by releasing the information to international committees related to radiation. However, it seems that there is a long way to go, as their political power is weak. Even at this moment, the victims in hospitals in the Reservation are being interviewed. They are under special ‘care’ of the government. In the hospitals in Navajo Reservation, there are doctors dedicated to treatment of uranium miners and their families. They meticulously record all the details of diagnosis and progress. The details will never be released until they are declassified by the U.S. government in the future. It is a subject of special care, as it is a highly sensitive issue. |

|

| ARCHIVE |